Remembering ‘Hammerin’ Hank’ Aaron

by David Cross

I can still smell the aroma of roasted peanuts and still see the faces of the Black men offering them for sale to the fans walking through the narrow streets of their neighborhood on the way to Crosley Field to see what would soon be known as “The Big Red Machine”.

To a 12-year old baseball fan from Albany, Kentucky, it was a memorable experience. But the entire day was.

Mike Watts, or “Brother Mike” as he was known to all- the young, dynamic pastor of Albany’s First Baptist Church, had organized a trip for the church youth, and others who could fit on the bus, to go to Cincinnati to see a major league baseball game on Saturday afternoon, May 16, 1970.

I had never been to a big league game. I had seen them on TV, starting when Pee Wee Reese (he was George Hancock’s bird-hunting buddy-he actually came to our house to use the telephone once) and Dizzy Dean did the Saturday afternoon “Game of the Week” on CBS. Through 1964, the Yankees were winners, and I started to be a Yankee fan. But in 1965, they finished sixth and were worse in 1966.

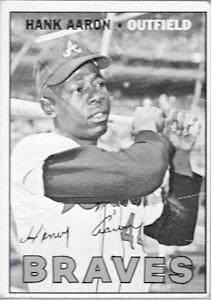

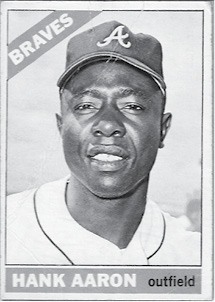

1966 was the year that the Milwaukee Braves became the Atlanta Braves. Atlanta was a long way off from Albany, so I didn’t think much about it until one Sunday afternoon we turned on the TV (we just got three Nashville channels in those days) and-wonder of wonders, the Atlanta Braves were on TV. WSM-TV in Nashville had decided to carry some Braves games during the season. Their pitching wasn’t very good, but they had a good hitting club with Felipe Alou and Rico Carty and their best hitter, Hank Aaron. My brother and I had all their baseball cards, purchased either at Chilton’s 5 & 1O or McWhorter Variety.

Hank Aaron, “The Hammer’ as announcers Milo Hamilton, Larry Munson and Ernie Johnson would call him, was the best.

That’s when I became a Braves fan. I followed them the next several years, watching Hank lead a Braves team that struggled to reach .500 nearly every year. I watched the pursuit of Babe Ruth’s home run record and was proud when Hank hit Number 715. I was sad when he was traded to Milwaukee for the last two years of his playing career, but as a 17-year old, I sort of understood, as that’s where Hank had spent most of his career, leading the Braves to back-to-back pennants in 1957 and 1958 and winning the Series that first year.

So that Saturday in May 1970 was extra-special for me. The Braves had won their division the previous year, and Rico Carty had a 31-game hitting streak on the line that Saturday afternoon. But Aaron was the attraction for me: he had 2,997 hits and with a big afternoon could reach that magic number of 3,000.

Jim McGlothlin started for the Reds against Braves knuckleballer Phil Niekro. Things didn’t turn out so well for the Braves, as McGlothlin spun a complete game shutout, the last one in the history of Crosley Field, and the Reds won 2-0. Carty’s hitting streak ended, and Aaron hit two doubles, giving him 2,999 hits. He never got back to the plate, however, and didn’t get Number 3,000 until the next day.

Aaron finished with 755 career homers, which stood as a record until the juiced-up Barry Bonds passed him. The Braves never made it to a World Series for over twenty years. The Reds traded for Joe Morgan and dominated for a few years.

Aaron, who had played in the Negro League and faced racist taunts and threats during his career, was nevertheless always a perfect gentleman, on and off the field. When the Braves moved to Atlanta, race relations weren’t good in Dixie, but every home run Hank Aaron hit made him grow in stature to thousands of little Southern white kids like me. He was the first African American sports hero for so many people, including me.

Hank died last week at age 86, just a few days after his teammate and fellow Hall-of-Famer Phil Niekro. He was a champion in everything he did, despite being brought up as a poor Black kid attending segregated schools in Mobile, Alabama, and hitting cross-handed because nobody ever told him not to. Hank thought America was a wonderful country, a land of opportunity, but also knew that America still has a way to go regarding race relations. He knew there were still too many of his race selling somewhere outside the ball park.

We still follow the Braves at my house, thanks to WSM and Hammerin’ Hank Aaron. I tell my kids that Freddie and Ozzie and Ronald are great players-but Hank was, and will always be, #44 in my program, but Number One in my heart.

David Cross