Work at Wolf Creek Dam continues, but Corps says the end is now in sight

by Alan B. Gibson

Clinton County News Editor

One of the hardest tasks to accomplish is to stop a leak in any structure that has significant age, and for the past several years, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has been working, and spending millions, in an effort to accomplish just that at nearby Wolf Creek Dam.

Since 2006, after it was announced that a significant amount of water was seeping through and underneath the mile-long structure just north of Clinton County, the Corps has been attempting to stop the flow of water and once again make Wolf Creek Dam a safe structure.

That attempt has included a process of pumping a grout material into the cave-filled, or karst, geometry Wolf Creek dam was built upon in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

That grouting effort was made to fill voids that lie out of sight, but not out of mind, below the surface of the dam, and make way for the next portion of the rehabilitation project, the construction of a concrete barrier wall that would be installed on the Lake Cumberland side of the earthen portion of the dam, and extend downward to a depth of 275 feet below the normal summer pool level of the lake.

During the entire construction process, motorists on U.S. 127, which travels across Wolf Creek Dam, and boaters on Lake Cumberland, have been watching as construction crews built platforms and later drilled into the structure to pour the concrete barrier wall.

While the process has continued nearly non-stop for the past five years, official updates from the Corps have been somewhat sparse, at times fueling the local and internet rumor mills about problems with the structure, movement below the surface and even the tale of significant increases discovered in the amount of seepage.

An update given last week by Corps of Engineers officials offered local and regional members of the media the opportunity to hear first-hand that not only is all apparently going well with the Wolf Creek Dam rehabilitation project, but in fact, the end is perhaps now in sight.

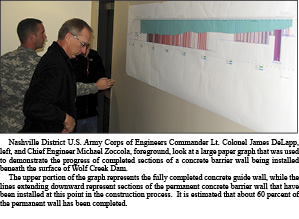

Lt. Col. James A. DeLapp, the Commander and District Engineer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Nashville District is a relative newcomer on the scene with the Wolf Creek Dam rehabilitation project, arriving at the Nashville District Office just five months ago.

Last Friday morning, DeLapp told a group of about 25 members of the media that not only is the project on schedule for it’s planned completion date, but ways to shorten even the remaining span between now and the final stages of the project were being looked at.

“The project is still on schedule to be complete by December, 2013, allowing the rains in the winter and spring of 2014 to fill it back up to its normal level and we will resume normal level operations in the summer of 2014,” DeLapp said during the initial moments of his briefing to the media at the National Fish Hatchery just below the earthen portion of Wolf Creek Dam.

Currently, Lake Cumberland is operating at a depth of 680 feet above sea level, more than 40 feet below its normal summer elevation of 723 feet above sea level.

DeLapp spent several minutes early in the presentation, assuring that the Wolf Creek Dam project was of utmost importance not only to the immediate area, but especially to the Corps’ Nashville District office.

“This is the most important project in our district,” DeLapp said. “This project is of utmost importance to the region, not only in terms of an economic standpoint, but obviously also from a water resource standpoint as well as from a flood prevention standpoint.

The Lt. Colonel also emphasized that ensuring the integrity of Wolf Creek Dam would guarantee communities and residents downstream were safe was of utmost importance to the Corps as well.

DeLapp was one of three Corps officials who spent several hours Friday morning dispensing information about the progress of the project and guiding a tour of the actual construction work area as drilling and material moving continued.

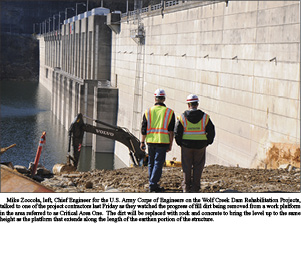

Mike Zoccola, the Chief Engineer for the repair project at Wolf Creek Dam, and David Hendrix, Project Manager, were also on hand to answer questions and outlay progress information about the process.

Zoccola explained again why the rehabilitation project had become necessary in the first place, noting that an attempt to stop seepage discovered in the 1960s and 1970s, as it had turned out, had not been thorough enough to remain in place as a permanent fix.

Zoccola referred to the caves and voids in the karst geology underneath mentioned earlier in his explanation as to what had caused this problem to occur again.

“The water from the lake, over time, has moved through those features and eroded some of the materials out and if you don’t take care of that, the dam can collapse into that, like we had back in the 60s.”

It was during the 1960s that large sinkholes were discovered in the earthen portion of the dam, as a result of material underneath the surface having been washed away by the water moving through the caves and other voids.

During the earlier grouting work, an area known as “Critical Area One” has most often been the source of problems encountered by contractors attempting to fill the voids in the structure’s subbase, and a host of different methods and grout formulas were tried, all with much less than favorable results.

That area, Critical Area One, was the worst of the problems regarding the dam’s seepage.

Situated in the area where the concrete portion of the structure meets the beginning of the earthen portion of the dam, the geology beneath the Critical Area One contained not only the small voids and caverns that had been found beneath all along the earthen structure, but also several large caves that were documented in photographs taken during the actual construction of Wolf Creek Dam in the 1940s.

The news that everyone has been anxiously awaiting to hear for several years, became official last week when it was announced that the grouting in Critical Area One had now in fact been successful and that the full attention of the contractors would move toward the final barrier wall installation.

“We just completed grouting in Critical Area One,” Zoccola announced to the media Friday morning.

Zoccola also explained the equipment that was being used, and the process involved in placing the concrete barrier wall down through the embankment and into the solid bedrock some 275 feet below the surface of the work platform.

That wall is currently well on its way toward being completed, and is being installed by Trevilicos Soletanche JV. It was pointed out that world-wide, only a handful, as few as four or five companies, have the ability to handle a task such as installing the barrier wall at Wolf Creek Dam.

In fact, the contractor on the job at Wolf Creek, is actually a partnership that was formed between two of those contractors, one a French firm and one an Italian firm.

Two key pieces of equipment, and the two most noticeable on the work platform, are the two large drilling rigs that are used to drill into the dam and rock below, creating the area that will be filled with concrete to create the final barrier wall.

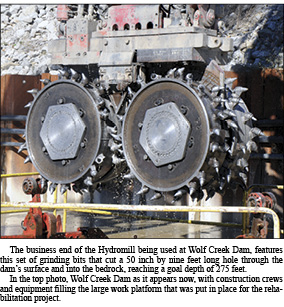

A Hydromill is used to cut out rectangular shaped areas that are 50 inches wide and approximately nine feet long, and a second rig known as a Worth Drill that drills out the round, 50 inch diameter holes into the bedrock.

Both drills have several hydraulic hoses attached, as well as a larger hole that is used to pump liquid material, or slurry, through, that is vital to the drilling process.

“The slurry is constantly pumped through the hoses to keep the hole open and at the same time, it is also pumped back to the surface as means of getting the cutting waste back to the surface,” Zoccola said.

The large teeth on the cutting wheels that dig through the rock material, can be removed and changed, depending on the application as to what type of material the rig is grinding through at any particular location.

“The cutting head is about 60 feet long, filled with lead shot and weighs about 60 tons, with the weight designed to provide tremendous down pressure as the drill rig works through the materials to the bedrock foundation as far as 275 feet below the surface,”Zoccola said in describing the mammoth size of the Hydromill.

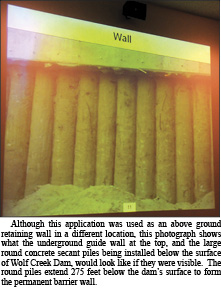

The process begins with the removal of material to a much shorter depth for construction of a guide wall that is used to insure the drills are able to begin working through a good solid surface, preventing the equipment from getting away from a near perfect vertical path.

That initial wall is referred to as the Protective Concrete Embankment Wall, is in essence, a guide wall, and is an important part of the permanent wall that will be installed at a later time, although for the most part, much of that guide wall will eventually be drilled out and disposed of during the process of putting in the permanent barrier wall.

Pilot holes, eight inches in diameter, are then drilled through the guide wall, and are used by the large drills during the cutting process prior to the pouring of concrete into the large holes created for the permanent wall.

“The eight inch diameter pilot holes are drilled to a depth of close to 300 feet, with a deviation on the order of six inches or less . . . within a few inches, we’re able to drill a hole almost the depth of a football field and not deviate at any point more than a few inches,” Zoccola said. “That’s easy to say, but it’s awfully difficult to do, but it is critical in doing with this type of barrier wall.

The permanent barrier wall being installed is a multi-step process that will eventually see a series of overlapping concrete structures, some round and some rectangular, extending down to the desired depth of 275 feet to cut off the flow of water currently going through and underneath the dam.

The round piles, referred to by Zoccola and others as “secant” piles, are some 50 inches in diameter and are constructed in alternating fashion leaving a space in between in the first stages.

When the secant piles are drilled out and poured in between the first one installed, they are done so on spacing of 35 inches center to center, so that at no point along the permanent barrier wall, is the thickness ever less than 24 inches.

When the secant, or round piles, are used in conjunction with the overlapping rectangular patterns, that combination is referred to as a “dog bone” form.

Zoccola explained that it was mainly left up to the contractor to decide which method to use, the series of overlapping secant piles or the combined dog bone fashion method, except in the area known as Critical Area One.

The Corps insisted on using the circular or secant pile, style of wall in the area of the dam referred to as Critical Area One, and it turns out that decision is mainly a safety issue.

Because of the larger number of voids and the large caverns that are already known to exist in that particular area, the Corps realizes that the risk factor of one of those voids opening up during the drilling process is much greater than in other areas of the dam.

“It goes back to the slurry issue – if we are going to lose slurry, we want to lose it out of a 50 inch diameter pile, rather than a big rectangular panel, because of just the size of it,”Zoccola explained.

Presently, much of that process has been completed with the permanent barrier wall being in place along much of the dam’s length.

With the completion of the grouting in Critical Area One, the work will now continue to advance toward that portion of the structure, and it was pointed out that being forced to wait longer than expected to install the permanent barrier wall there, was perhaps a blessing in disguise.

As the contractor now approaches that most critical and dangerous area of the dam, they now have years of experience in installing the barrier wall along other portions of the dam, and won’t be learning the best process while working what is considered the most vulnerable area.

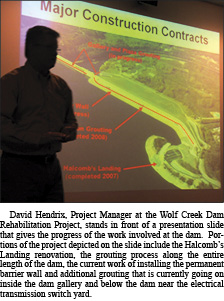

Hendrix pointed out that at this point in the construction timetable, the wall installation portion of the project is about 60 percent complete, and in considering the entire project, including the grouting and the construction of the new Halcomb’s Landing ramp and parking area, the entire rehabilitation project is about 70 percent complete.

The Halcomb’s Landing portion of the project was the first completed and was necessary in order to give construction crews an area known as a “lay-down” area for equipment maintenance and storage, as well as better access to the work platform area.

Currently, crews are busy removing dirt fill material that was previously put in place for the first contractor doing the grouting work near Critical Area One.

That platform, as it turns out, is much too sloped and too narrow for the equipment being used by the current contractor installing the permanent wall. The fill material will be replaced with rock and concrete and will bring that area of the platform up to the level of the rest of the platform now being used.

When the rehabilitation work is finally completed, Hendrix noted that the dam will more or less be returned to it’s original appearance, with the work platform being removed, and replaced with the large rocks, or rip rap that was in place prior to the start of this latest construction project.

At last week’s stage of production, the total cost of the Wolf Creek Dam repair project is listed at $584 million, with some $341 million having been spent at this point.

Zoccola and Lt. Col. DeLapp also touched on the condition of another dam that is on the minds of Clinton County residents and also in the Nashville Corps of Engineers district, Dale Hollow Dam.

The Dam Safety Action Classification (DSAC) is a level rating for each of the dams, and Wolf Creek Dam and Center Hill Dam are each rated at DSAC Level One, which is the worst condition,” DeLapp said.

DeLapp said that a rehabilitation project similar to the one currently being completed at Wolf Creek Dam, was just now in the initial stages at the Center Hill Dam.

Zoccola told the Clinton County News that while no man-made dam can ever be considered as problem free, the dam located at Celina, Tennessee that is responsible for impounding Dale Hollow Lake, has problems, but nothing as serious as the problems being corrected now at Wolf Creek Dam.

“A five rating is perfectly safe, no problems whatsoever, and you just never really have that with a dam – you can never say that everything is fine, so Level Four is the lowest classification that the Corps currently has right now,”Zoccola said. “Dale Hollow has similar problems (to the seepage problems at Wolf Creek Dam), but they aren’t dam safety problems because Dale Hollow is an all concrete dam, so you don’t have the concerns like you have here with the earthen embankment.”

He further explained that the seepage problems at Dale Hollow meant that water would flow under the dam structure and end up under the electrical switch yard below the structure.

“That could cause sinkholes underneath the switch yard that equipment could fall into and we could lose our power capability, but as far as the loss of the project, there is no concern there,”Zoccola said.

According to all three officials at Friday’s briefing, the bottom line was the reporting of some very positive developments – that not only could the Corps say that the completion of the project was in fact now in sight, but that a return to normal lake levels on Lake Cumberland was likely to be experienced by the summer of 2014.

Most importantly, however, was the message that the measures being taken to return the integrity of Wolf Creek Dam to a safe level, were working.

“There’s no question that the dam is much safer than it was back in the 70s, and its much safer than it was two years ago or four years ago . . . no question about it,”Hendrix said.